Dissolving the Boundaries

An Interview with Tanya Krzywinska

For the Newlyn Society of Artists Exhibition Engage

The words and images I use come together in a kind of visual poetry. I’m interested in the landscape as a living, pulsing, needing thing and blurring the lines between the domestic and the natural.

Tanya’s studio, an outbuilding to her granite farmhouse, is light and richly decorated. Ornate rugs, squashy leather armchairs, shelves swollen with books, drawings and paintings cover the space. These pieces range from minimal figurative drawings to verdant paintings of dilapidated dwellings. Small objects catch my eye. A cluster of tiny chairs commune on her windowsill. Toy cars rest on her shelves and a large dolls house stands on a table in the corner of the room.

We launch straight into discussing the show. Tanya is energetic, fizzing with ideas and knowledge, chatting merrily and intellectually about her many consecutive projects. Her role as professor of Digital Games at Falmouth University, where she conceptualised and coordinated a slew of Game design MAs and BAs is immediately evident. Here is someone who knows what she is talking about. Her speech is naturally academic, with no strain of pretention, her brain clearly operating at a high velocity.

KRE: Why did you want to introduce digital technologies to a selection of NSA artists for this show?

TK: I’m particularly interested in the interface between the digital and the material and the new technologies which enable us to do that. There is digital-only art, which uses simulacra of how paint works (see David Hockney’s iPad drawings). For me, this form of entirely digital art feels airy and unanchored. I am more interested in when the digital comes into contact with the material. I like things to be partly in the world because it gives the experience ballast. The imaginary and the real intermesh, creating an amazing landscape of aesthetic affordances.

There are very simple tools you can use to engage with new technologies, especially Augmented Reality (AR) so I wanted to show other NSA artists what the possibilities are with low-end accessible tools.

Artists are supposed to make people look at things in a new way and the capacity to do this with AR is enormous. Art occupying spaces other than a gallery wall creates the possibility of engaging new audiences.

KRE: Why do you think this was particularly important for the Passmore Edwards Centenary Festival?

TK: Cornwall has always been a place of innovation and technology, from leading developments arising out of the mining industry to the St Ives Modernists. Passmore Edwards is a part of this history of innovation. He encouraged education and inclusivity, building physical structures and infrastructure to facilitate community outreach. We can learn from Passmore Edwards’ philanthropy, that it’s important to give back to the social dimension of our culture. I’m interested in getting people involved with digital art who think there is a barrier to entry. Increasingly, this barrier is becoming more malleable.

One of my other ongoing projects is developing an app for children who have suffered trauma, which will use art practice techniques within it. The app will be a game which will help children articulate their own trauma. Digital technology can provide a private and absorbing space for children with traumatic experiences to access and have ownership of.

KRE: What is the piece you have created for the NSA Engage show?

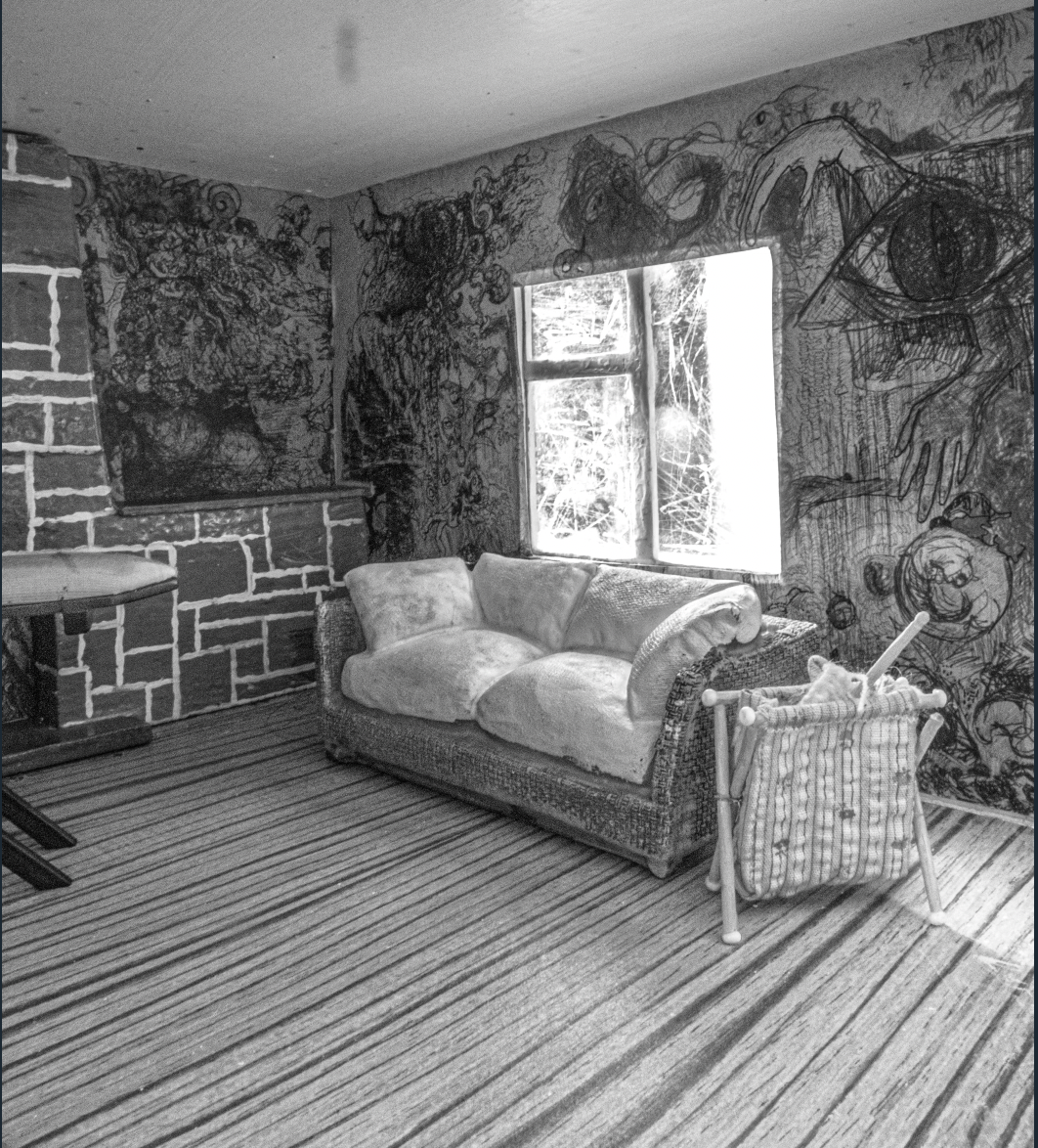

Tanya takes me over to the dollhouse. On closer inspection, what looks like heavily patterned wallpaper covering the minute walls, is hundreds of detailed drawings. These drawings are highly illustrative, inky black and intriguing. Creatures blossom out of them: crows, red-eyed monsters, and shifting black masses. Tanya explains that she becomes restless when sat still for long periods of time and needs something to do with her hands, so, whilst in meetings, she doodles on bits of paper.

This wallpaper is the result of layering these collected scraps on top of each other.

Tanya takes her phone, hovering it over each room. Through the screen a pulsing mass of coloured particles pulse and swells. She moves to the hall and reveals a crow flying directly towards the viewer. In the next room, ragged red words ‘the charms wound up’ materialise before dissolving. Downstairs, the word ‘bat’ is repeated hundreds of times, forming itself into leaves of a breathing auburn tree.

TK: Augmented reality is three-dimensional, allowing you to move through space and create a kind of environmental storytelling. The way AR works is that it reads images like QR codes, pulling up the animation and layering it on the space. I take photographs of each room, inputting these into the AR application, then link them to the animations I have created. When your phone hovers over the room in the correct way, the animation appears.

KRE: Can you expand on what inspired the animations?

TA: They are kind of hauntings. A lot of what I do references Folk Horror; many of the core texts, ‘The Wicker Man,’ ‘Ritual,’ ‘Blood on Satan’s Claw,’ are set in Cornwall. These narratives surround the fear of nature and the rural. With my work, I borrow from the vocabulary of these narratives. I don’t seek to tell a narrative story, rather the words and images I use come together in a kind of visual poetry. I’m interested in the landscape as a living, pulsing, needing thing and blurring the lines between the domestic and the natural. I’m fascinated by the texture of difference between the inside and the outside. When we cross the boundary of the domestic, we are crossing both emotional and psychological borders. I’m drawn to dwellings where this boundary is being dissolved, where humanity’s mark is being overtaken by natures incredible energy. The domestic turned wild is a breach of the categorisation.

I mentioned to Tanya that I had never tried virtual reality before so, after the interview, she took me into her study and introduced me to VR. With the headset on, you become entirely absorbed. I saw a sunset dipping below a snow-crested mountain, trees with leaves blowing in realistic gusts of wind, a whale sored over me, huge and steady, I even went to space. Tanya showed me how the ‘hands’ worked, and I learnt how to throw ping-pong balls, which bounced exactly like real ones. I could shoot toy rockets into the atmosphere and hold solid shapes in my hand. She put on a programme called ‘Trip,’ a kind of calming aid, where I was instructed by a disembodied voice to breathe in and out. As I inhaled, shining yellow particles flowed into my mouth, on the exhale they were pushed back out, now a glowing blue. Kaleidoscopic shapes and colours bloomed and morphed in front of me. They pulsed and changed, and I couldn’t help smiling. After an hour or so of playing with the VR headset, my eyes had been opened to a tool which not only aided absorbing story telling but has the potential to provide a calm space and respite from the outside world.